Here is a place I have found an unexpected cross.

Milliken vs. Morin in the South Carolina Supreme Court

A couple weeks ago, the South Carolina Supreme Court issued their opinion on Milliken vs. Morin. The opinion can be read here.First, please understand I am not a lawyer and so am writing my own unprofessional opinion and observations. If this posting or its content has any meaning in your life, I suggest you get an attorney as the subject matter is quite confusing.

They "AFFIRMED AS MODIFIED" the prior court's opinions. Let's be clear, here: I was asking them to overturn the jury's verdict as a matter of law. They declined to do so, which in every day language means that I lost and Milliken won.

The justices begin their comments on page 11 with:

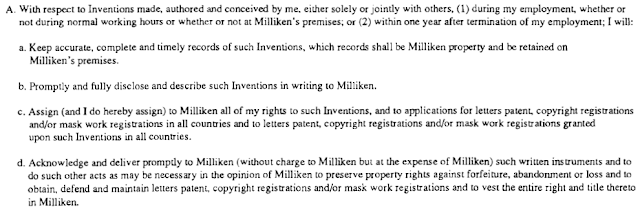

The invention assignment agreement Morin signed is embodied in a complex set of paragraphs which by no means are an exercise in clarity. After sorting through the morass, however, the impact of the agreement is much narrower than it may appear initially.

There are three important clauses:

Together these are pretty broad. But on the next page is this:

These make up the "morass" that is "by no means an exercise in clarity" and "much narrower than it may appear initially."

Back in college, I had a class in Digital Circuits so I thought I knew something about AND and OR gates, but admittedly can get confused with a complex series of nested AND, OR, NOTAND and NOTOR gates.

Back in college, I had a class in Digital Circuits so I thought I knew something about AND and OR gates, but admittedly can get confused with a complex series of nested AND, OR, NOTAND and NOTOR gates. In this picture, the big blue circle is all inventions authored by the employee. These belong to Milliken, except what is excluded by the exception. The exception has phrases A, B, C1 and C2 represented by the red, purple, and two green circles. I had thought the exception applied to inventions which satisfied

A AND B AND (C1 OR C2)

Now look again at the picture. In my interpretation, the exception would include only the little quadragonal type shape and the tiny triangles next to it--a little rabbit head--everything else in the big blue circle belonged to Milliken. The justices state early that:

This argument is based on a misreading of the agreement.In their opinion, they state:

Under the terms of the agreement, if the invention either does not relate to Milliken's work or was not the result of work performed by the employee for Milliken, then it is not covered.This is broader than the little rabbit head. The justices go on:

Conversely, for the exception to not apply— and thus require assignment of the invention—it must both relate to Milliken's business/research and result from the employee's work at Milliken.Then, to leave no ambiguity, they add:

Thus, so long as the invention does not relate to work performed by the employee, it is not to be assigned.So the exception applies to everything except areas that are both related to their business and result from the employee's work at Milliken. In this picture, both green circles are now excepted from the assignment. The exception applies to inventions which satisfy

C1 or C2For complete clarity, they state:

Under general principles of contract law, we find first as a matter of law that this agreement is unambiguous.To be clear here--this is not a criticism of the Justices or their ruling. In a complex nesting of logic gates there are plenty of ways to cancel one with another and it's honestly beyond my capability to understand whether you can get from the "morass" to where they arrived. They did; it is now law. That is fine and just and good and I would expect no less from our court system.

A Personal Note

A portion of my life has been scrutinized through the lense of this agreement for seven years. Every word in thousands of pages of notebooks, emails, notes and correspondence were held up to the standards laid out by this "morass" that is "by no means an exercise in clarity."

All of this was presented to a jury and they found that my actions did not live up to this standard. I only got a B+ in my Digital Circuits class and trust in the wisdom of the jury to have hit pretty close to the mark. They found that I had caused $25,324 of damages to Milliken. It has been paid.

To obtain this verdict, Milliken expended valuable resources (likely millions in outside attorneys, plus internal resources, but it could be less or more).

And now we find much of what we argued about was "based on a misreading of the agreement," and that "the impact of the agreement is much narrower than it may appear initially."

God is in there, for sure. Using this thing to work on both sides, I believe.

Many people have hypothesized what purpose compelled Milliken to expend these resources. Most fall in three categories: 1) that the inventions in question are so valuable that the chance to obtain them was well worth the expense, 2) that they had to make an example of me to keep an iron fist on their employees, or 3) that there was a personal vendetta against me by some managers of Milliken.

Each seems difficult to believe on one level or another. I think rather they thought they were right, and weren't going to back down. I respect that, and respect the people involved.

If the question is posed spiritually the answers are far easier to find, for they rest in the love of a God who has great plans for me and them, and needs us all to become more than we were or are. To this I submit with gratitude, and I know several of the gentlemen on the other side do as well.

I will finish with three Bible verses, assigned this morning to my seven year old daughter for her weekly reading.

James 1:2-4

2 Dear brothers and sisters,[a] when troubles come your way, consider it an opportunity for great joy. 3 For you know that when your faith is tested, your endurance has a chance to grow. 4 So let it grow, for when your endurance is fully developed, you will be perfect and complete, needing nothing.1 Peter 1:6-7

6 So be truly glad.[a] There is wonderful joy ahead, even though you have to endure many trials for a little while. 7 These trials will show that your faith is genuine. It is being tested as fire tests and purifies gold—though your faith is far more precious than mere gold. So when your faith remains strong through many trials, it will bring you much praise and glory and honor on the day when Jesus Christ is revealed to the whole world.Romans 5:3-5

3 We can rejoice, too, when we run into problems and trials, for we know that they help us develop endurance. 4 And endurance develops strength of character, and character strengthens our confident hope of salvation. 5 And this hope will not lead to disappointment. For we know how dearly God loves us, because he has given us the Holy Spirit to fill our hearts with his love.