"Daddy, could you come protect me from bees while I get this apple," Alex asked me.

"Certainly," I told her. "I am a great protector from bees." And so she took my hand and pulle me into the apple tree, with bees bzzzzing from one fallen and rotting apple to the next, gathering whatever it is they gather that eventually turns to honey. With some lifting and climbing and one "swish!" at a bee that got too close, she gained her prize--a golden delicious apple that was a little bigger, a little plumper, a little juicier than the others. Then it was down and off to the next one.

In this next series of posts, I'd like to talk about the core functions of the startup CEO. In some cases, it will be the actual activities of the CEO, in some cases responsibilities--what I really want to capture is the essense of those things that

can not be delegated, that fall foremost and only into the lap of the CEO, that she and she alone can cause to be accomplished, and that without her

will fail with absolute certainty.

Daring Greatly

The first has been described quite well in a quote from Theodore Roosevelt:

It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without error or shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself for a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat.

And so the startup CEO must

Dare Greatly; she must be in the arena, with dirt marring her fingers and sweat traversing her brow, making things get done that otherwise, without her courage and pathalogical fearlessness, would go undone, would fail unaccomplished, would wither unnourished.

The CEO must choose these great goals, and this is not about the distinction between organizing the world's information, putting a computer on every desk, stopping bullets, solving the world energy crisis, increasing marital harmony, bringing people to God, or other great tasks. The question here isn't the

direction of the walking, it is the

length of the stride. And that stride must be GREAT!

How to do it Wrong

In my early career, my work on many projects made tiny strides:

- Reducing the dust on wipers for cleanrooms.

- Adding the ability to put a color pattern onto the seat backs of cars inexpensively.

- Making a small, strong fiber to reduce weight in technical apparel fabrics.

- Making a smaller fiber that felt nicer in apparel fabrics.

- Making a carpet backing that would go a little longer before it had to be restretched.

- Making fiber process faster.

In each of these, there was the potential to make money, and in some cases, a lot of money. But each was a nuance on what had come before, something that people might pay for, but otherwise would make very little difference.

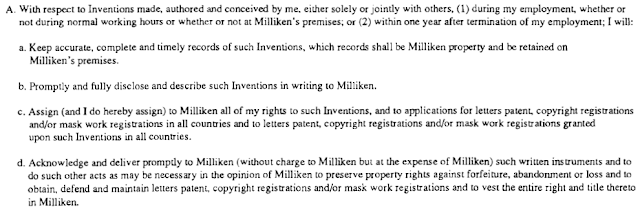

I can remember one instance in particular where I was championing an innovation that a group of us had had. John Rekers, the Division President for the Chemical Division at Milliken, had asked us to make a 50% improvement. We had achieved about 30%, and I was challenging him to declare it "good enough," and let us move on with commercialization. John didn't answer my challenge, but rather turned the question to me, asking how we could make it better, how we could reach farther, improve it further. What had we left unexplored? What paradigms had we not challenged that would uncover the key to making this bigger stride?

After I left, this group did achieve their 50% improvement, and did launch a product, and it appears from the outside to be doing quite well. John had the capability to demand great strides. This example illustrates clearly the leader he was, and that I wasn't.

One way to do it Right

Early on at Innegrity I knew the fiber was

really different, but I was still trying to use it to make canoes and kayaks a little lighter or a little less expensive.

During this time, two people ask me the same question in different ways. One asked if it could work to make the fastest, most highly engineered cars in the world perform better. I said no, I didn't think so, but he asked if he could try anyway and I told him go ahead. He did, and it made the cars lighter and the team we were working with went from 9th to 1st (of 12 teams) in one season using our fiber, and that became our first commercial success.

The other person asked if it could be used in ballistic protection, and I said no, probably not, it's not strong enough, but go ahead and try. I can still remember landing on the tarmac at Reagan Intl Airport and trying to look at his data on my Blackberry and almost falling down the stairs with my VP Sales as we could not believe that it had outperformed Kevlar in many ways.

These two innovations--combining the fiber with carbon fiber in composites and combining the fiber with aramid (Kevlar) fiber for ballistic protection--form the cornerstone of Innegra's success. As a practitioner, I said "No, don't bother." As a leader, I asked, "Do you really think so?" and "What would happen if it were so?" and I created an environment and gave them the time and resources to try, to

Dare Greatly, and when they did, I helped to leverage their success into many more successes, and ultimately turned a spongy little fiber into something that has won multiple world championships in several different sporting arenas and has been placed into a position where it can save lives.

One Difficulty

As Mr. Roosevelt pointed out, one difficulty with

Daring Greatly is the critics. I used to joke that in some venues, the smartest people in the room are those who are able to articulate their ignorance most eloquently. "I don't know if we have properly considered the consequences of implementing such a technology, and whether it might cause great damage if it were in such-and-such a situation about which we have no knowledge at all!"

At its best, this criticism is a background buzz that nags and slows and builds unnecessary fear, hindering the feet of those who would take great strides, causing their steps to shorten and their footing to grow less sure. At it's worst, the critics take up the mantle of a crusade to destroy change, pouring energy and resources into building fear and breaking down what strides have been made.

In the end, the leader has to understand the cowardice that runs through the veins of "these cold, timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat," and stride on anyway.

A Postlude

Alex picked her apples. She climbed her trees and selected the ones that were

just so. Later, she rode on a hayride and dressed a scarecrow and played and jumped and ran with her brother. Then, when we sat down for lunch, she did get stung by a bee for the first time in her life and cried great tears with big belly whelping sobs erupting like so much lava. An hour later, she was laughing at her

stoopid daddy who told her that when he was a boy, he would shake bees in a jar to make them mad and then open the jar and run off, and sometimes get stung. When we got home, she ran next door to tell our neighbors about her sting and get their hugs show her wounds. But she still has her apples and she knows the joy of climbing and selecting and riding and dressing and running and playing, and she knows how little to fear the bzzzzing and even the stinging of the bees.

This

Daring Greatly is not the doing of a practitioner, though it can be. Rather it is simple, raw courage to break free of the world of the so-so, the hum-drum, the same-as-yesterday, and create something new--and not just a little new but

Greatly new. This

Daring Greatly cannot be delegated, it cannot be assigned, and without it any startup is doomed to mediocrity.